Self-care for the client/patient:

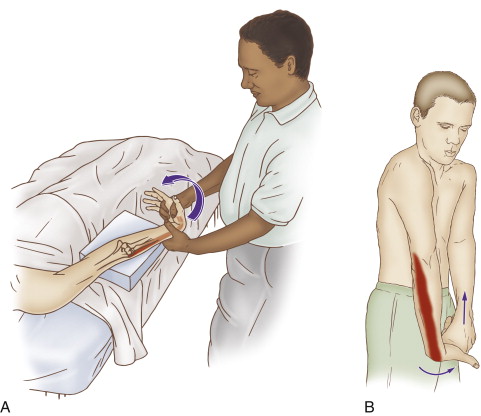

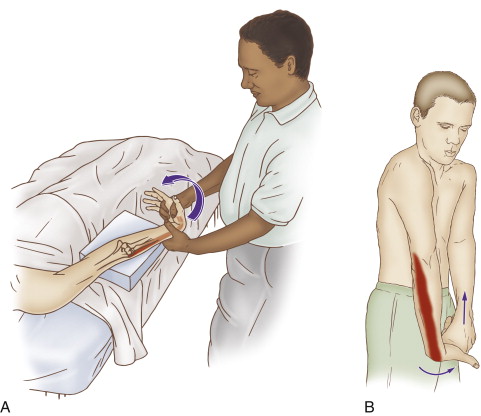

Self-care (and therapist-assisted) stretch for tennis elbow (for the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle). Permission: Joseph E. Muscolino, The Muscle and Bone Palpation Manual (2016), Elsevier.

Self-care is an extremely important aspect of the treatment for tennis elbow. The client/patient should be advised to avoid offending postures and activities as much as possible. Frequent stretching of the hand and fingers into flexion should be done. Some of the muscles of the elbow joint cross the elbow joint anteriorly (extensor carpi radialis brevis) and some cross the elbow joint posteriorly (extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, and extensor carpi ulnaris), so the elbow joint should either be fully extended (for the extensor carpi radialis brevis) or fully flexed (for the extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, and extensor carpi ulnaris) for full effectiveness of the stretch. However, if tears in the common extensor tendon are present, stretching should either be done gently or avoided. Further, stretching the hand at the wrist joint into full flexion increases pressure in the carpal tunnel, so may be contraindicated if carpal tunnel syndrome is also present. If the tennis elbow involves inflammation, icing should be done. Clients may also choose to take over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medication. If and when signs and symptoms of the condition have resolved, strengthening the forearm/hand musculature should be recommended.

Medical approach:

Whenever conservative manual therapy care is not successful, referral to a medical physician should be considered. Medical management usually involves prescription steroidal anti-inflammatory medication such as cortisone, as well as cortisone injections. If the degenerative phase is present, prolotherapy injections, including platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections are beneficial. Another approach is to “bleed the tendon.” This is done by repeatedly pricking the tendon with a small needle. As with prolotherapy injections, the goal is to stimulate a fibroblastic response to create fascial collagen scar tissue healing of the degenerated and/or torn fascial tendinous tissue. Note: When prolotherapy or bleeding the tendon is employed, the client/patient must avoid anti-inflammatory medication because it would halt the fibroblastic response and obviate the entire reason for this employing this approach in the first place. In worst-case scenarios, surgery may be done to remove degenerated collagen tissue as well as mend tears.

Manual therapy case study:

Glenn is a 42-year-old high school English teacher. Over the past year, he has noticed right forearm pain near his elbow. The pain has been getting steadily worse as the school year has progressed. He especially notices the pain when gripping the pen to grade papers. In the past few weeks, he has even experienced the pain when holding the steering wheel to drive to work. Glenn finally decided to seek care and went to a manual therapist who does clinical orthopedic work.

The therapist performed active and passive range of motion of the hand at the wrist joint. Active flexion and extension produced pain at the common extensor tendon, as did passive flexion; passive extension was asymptomatic. Active radial deviation against resistance also elicited pain. Palpation at the common extensor belly revealed tightness and pain. Palpatory pain was also found at the common extensor tendon and the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. The therapist also performed assessment tests for thoracic outlet syndrome and space-occupying lesions in the neck; these conditions tested negative.

Given the assessment of tennis elbow, the therapist recommended two one-hour massages per week for four to six weeks. Each session consisted of approximately 5 minutes of myofascial spreading, followed by 20-30 minutes of deep tissue work to the right forearm following the tennis elbow protocol (presented in Blog #4 on Tennis Elbow). The remainder of the time was spent working the rest of Glenn’s right upper quadrant with deep tissue work to the anterior forearm, arm and shoulder region; and moist heat, deep tissue work, stretching, and joint mobilization to the upper back, neck, and left upper extremity. Glenn was given self-care instructions including advice on how to stretch and ice the forearm. He was also given recommendations to avoid overuse of his forearm muscles, especially to avoid excessive gripping of objects. Because Glenn is a teacher and uses a pen to grade papers, he was advised to use a wider pen that has a rubber grip so that less strength is required to grip it.

At the end of six weeks, Glenn’s symptoms had abated approximately 80%. Care was continued at once per week for another six weeks to remedy the remaining symptoms. For proactive self-care, Glenn continues to receive clinical orthopedic massage once or twice each month.